Malaysia plunged into its latest stage of political crisis at almost the exact time that COVID-19 hit in March 2020.

The crisis began with the collapse of the centrist reformist “Coalition of Hope” (Pakatan Harapan, PH), which had come to power after winning the historic 2018 general election against the long-dominant conservative National Front (Barisan Nasional, BN). PH’s 2018 victory against a coalition that had been in power for decades helped show Malaysians that a change of government through democratic elections was possible. But one election alone did not bring the transformative change that was so desperately needed.

Then came their collapse. The PH’s brief stint in power came to an end as a result of what has since come to be called the “Sheraton Move”, a political maneuver to shift party allegiances planned by a number of members of parliament in the Sheraton Hotel on February 23, 2020. After months of disarray, the crisis reached a new zenith when the government that took over declared a state of Emergency and suspended parliament on January 12, 2021.

The political developments in Malaysia since the Sheraton Move have been extremely volatile, with a continuous realignment of political forces to stay in power or to keep other forces out of power. The relations between friends and foes can change overnight, but it has nothing to do with political principles. Instead, it is a battle of interests of different factions within the ruling class, each shuffling power among their proxies.

Political realignment at the top

In essence, the Sheraton move was a backroom deal among several MPs and parties to withdraw support for the ruling PH coalition. Following PH’s collapse in February 2020, a new coalition calling itself the “National Alliance” (Perikatan Nasional, PN) moved into power, and Muhyiddin Yassin, President of the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU), was sworn in as the 8th Prime Minister of Malaysia.

But the PN under Yassin’s leadership only held a very slim majority in the Federal Parliament. Politicians in PH, especially Anwar Ibrahim, tried to re-seize power by claiming that he actually commanded the majority — but this came to little result. The more serious threat to the PN government came from within. United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), a PN-coalition member that had dominated Malay politics from independence until 2018, pushed for a snap election in the hopes that they could restore their status as the dominant party within the ruling coalition.

Faced with an internal threat, and the potential collapse of the PN government, Muhyiddin Yassin declared an Emergency on January 12, 2021 — about the same time that the government reintroduced lockdown measures under the Movement Control Order (MCO). Though declared under the pretext of containing the spread of COVID-19, the Emergency’s clear purpose is to suspend Parliament and prevent the snap election from taking place. UMNO has decided that it will cut ties with PN as soon as the Emergency ends, and the snap election is likely to take place once the Emergency is lifted — but at least until then, political uncertainty will reign.

A Failure to Reform Leads to Crisis

Today’s crisis marks a preliminary end to a period of democratic opening that began with PH’s election in 2018. But the current situation also reflects the way in which the hope for democratic reforms in PH’s “New Malaysia” were shattered much earlier — after many U-turns and delays by the PH government in implementing reformist policies, and defections and betrayals among the politicians within the ruling coalition in their unresolved power struggles.

While the PH promised an extensive institutional reform in its 2018 election manifesto, it faced tremendous obstacles because of the conflicting political interests within its broad coalition. Apart from the sluggish implementation of reforms, the PH government did not represent a significant break in economic policy. The practice of collusion between the state and corporate interests was left untouched.

The government also failed to arrive at a consensus in alleviating Malay anxieties and cross-ethnic issues, allowing its political opponents to weaponize and continuously stir up racial sentiments for its own political agenda. Racial politics has haunted Malaysia since its colonial days, as it has been used by politicians, whether from the ruling or opposition parties, to mobilize ethnic-based support. Almost every single political issue can be racialized by those politicians with narrow political agenda — not for the liberation and equality of races, but as a tool of division to cater to narrowly-defined liberal ethnic interests.

Crisis: Political and Beyond

With the collapse of the PH government after less than two year after in power, the political landscape is once again being shaped by the shifting alliances of political factions rather than any reflection of democratic mandate. At the same time, Malaysia is confronted with multiple deepening crises. Beside the threat of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic and the political crisis, we are also facing the pandemic-induced economic downturn in the country.

The Malaysian economy overall has contracted by 5.6% in 2020, the worst performance since 1998 when the country was hit by Asian Financial Crisis. The official unemployment rate has risen to 4.5%, the highest since 1993. Malaysia’s Finance Minister, Tengku Zafrul Aziz predicted the economy of Malaysia to rebound by 6.5% to 7.5% in 2021. But given that Malaysian economy is still very export-orientated and driven by foreign investment, the Finance Minister’s absurd over-optimism just shows that policymakers and the political elites have no alternative vision of how to deal with the current predicament.

A real alternative is needed, and it has to come from the mobilization of progressive forces

With the ongoing political farce and tremendous challenges confronting the people of Malaysia, there is an urgent need to (re)build the social forces from below to bring about genuine alternatives and meaningful change. And there are reasons to be hopeful.

Before the historic election in 2018, Malaysia witnessed a number of mass mobilizations of ordinary people and civil society for over two decades. BERSIH, the coalition for free and fair elections, was one of the people’s mass mobilization that contributed to the struggle for democratic reforms.

Unfortunately, quite a significant section of the civil society was absorbed and co-opted into the establishment after PH came topower. Although some of them played a role in lobbying for reforms, a large section of the civil society has been demobilized. This demobilization means a lack of organized power in supporting democratic reforms and failure to respond to the increasing threat of reactionary forces mobilizing with narrow ethno-nationalist political agendas.

That’s why it’s crucial for the Left and progressive forces in Malaysia to rebuild a social movement that fights for genuine democracy and social justice — a movement that cuts across racial and religious lines. Movements and groups should do more to reach out across the ethnic divide, in order to be more sensitive to the problems faced by others, and continue to work towards a more inclusive and equitable Malaysia. With the current threat of the pandemic and economic downturn, we can rally ordinary Malaysians from different ethnic backgrounds into common demands for transformative social programs like the defense of our public healthcare system, against privatization of public services, job creations through our version of “Green New Deal,” and the introduction basic income scheme for the unemployed.

Today, Malaysian politics is defined by political infighting at the top. To build a new Malaysia, we must rise up as one from the bottom.

Choo Chon Kai coordinates the International Bureau of the Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM, or Socialist Party of Malaysia) and serves as the editor of Sosialis.net. He writes here in his personal capacity.

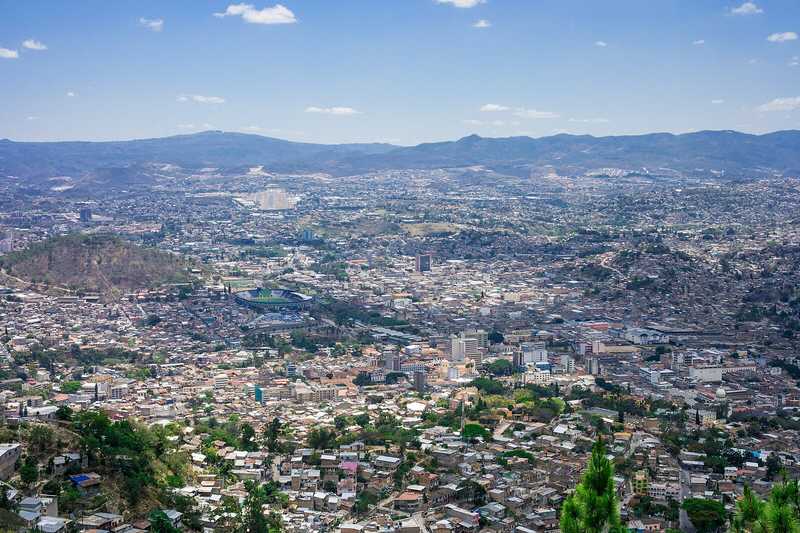

Photo: Hafiz Noor Shams / Wiki Commons